The story begins millions of years ago, when a few elements, heavier than others, started their journey from stardust and eventually ended up in our bloodstreams—making metals vital to life. Have you ever paused to think how the same iron that strengthens bridges also flows through our veins, powering our body? Or why copper, the go-to metal for electrical wires, plays a crucial role in our biological wiring too? The story of how these cosmic travelers ended up in our bodies, driving life’s most essential processes, is nothing short of spectacular. Let’s dive into the journey of these metals—from the fiery chaos of the universe to becoming life’s indispensable elements.

Long before Earth existed, the metals we depend on were forged in the heart of ancient stars. Stars act as cosmic factories, fusing lighter elements like hydrogen and helium into heavier elements like carbon, iron, and nickel. But the real magic happens when massive stars meet their dramatic end [1]. In a supernova—a stellar explosion of unimaginable power—elements like iron are hurled into the universe. Even rarer cosmic events, like neutron star collisions, create precious metals such as gold and platinum in dazzling kilonovas [2].These elemental riches scattered across space, in the form of enormous gas and dust clouds, eventually leads to formation of our solar system. As Earth took shape about 4.5 billion years ago, these metals became part of its very foundation, locked in its core and mantle. But early Earth wasn’t a quiet place.[3] Protoplanet collisions and constant volcanic activity helped bring some of these metals closer to the surface. Later, meteorites crashed into Earth, delivering even more metallic treasures. These metals weren’t just destined to stay buried in the ground—they would become vital for life [4].

So, how did these metals journey from lifeless rocks to living organisms? As life began to emerge on Earth, metals found their way into biological systems. Why? Their unique properties make them perfect for biochemical reactions. Metals can easily transfer electrons, making them powerful catalysts for energy production and other vital processes. Over billions of years, life evolved to use these cosmic leftovers as the building blocks for survival.

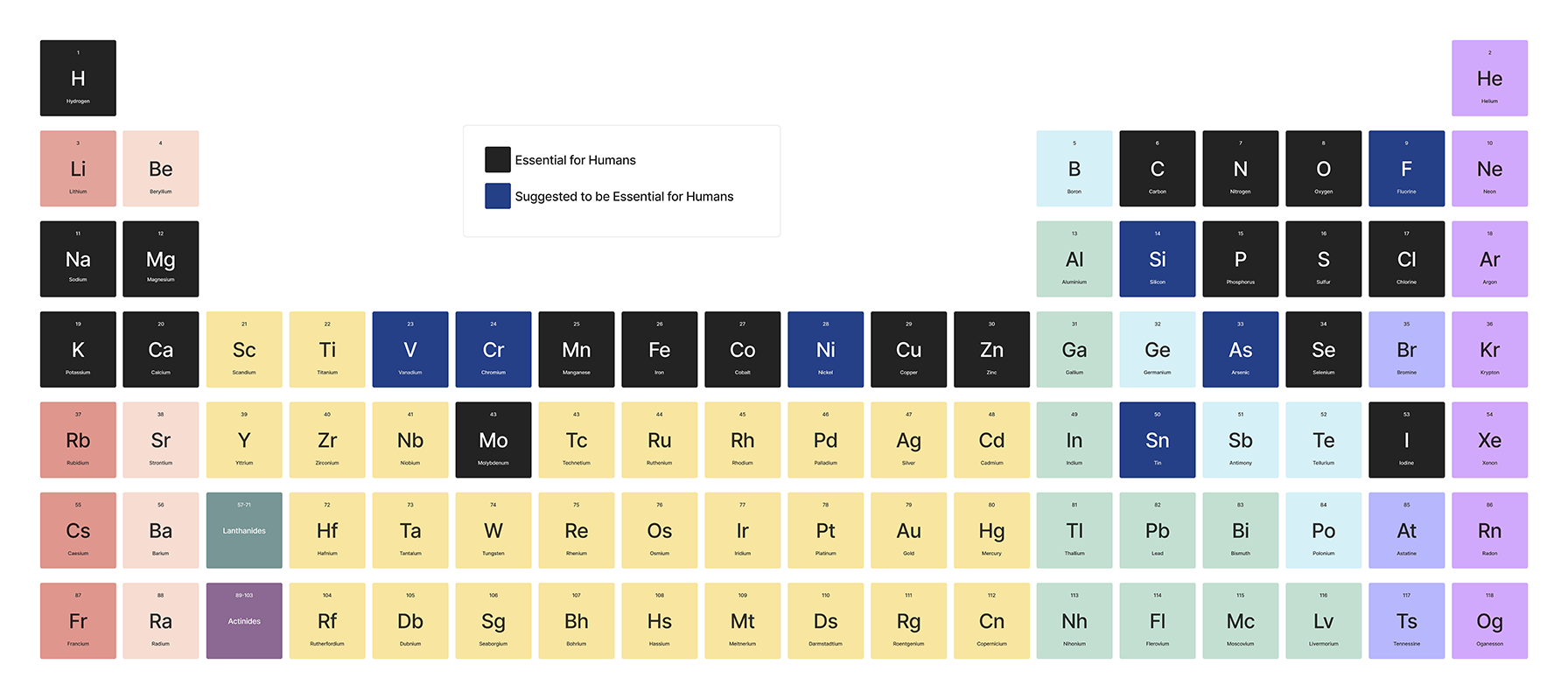

Take iron, for example. It became central to oxygen transport in blood. Magnesium was adopted to power cellular energy production. Copper was incorporated to protect cells from harmful chemicals. Metals didn’t just join the party—they became the backbone of life’s machinery.

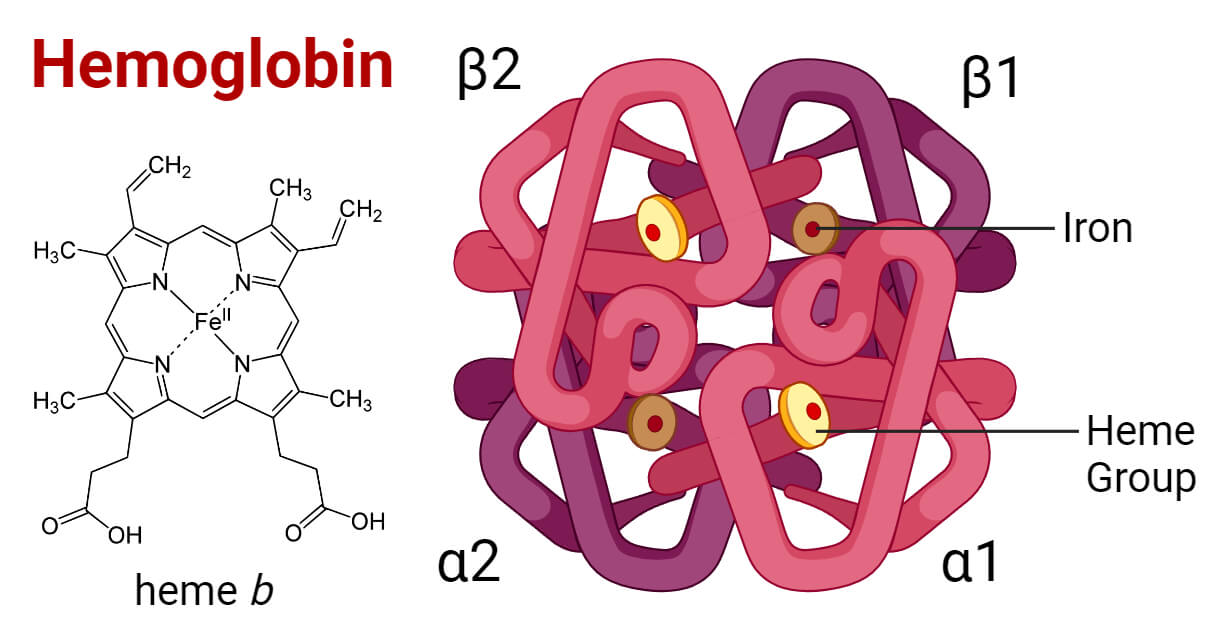

Naturally, the conversation must begin with Iron—the ultimate lifeline metal. Let’s start with breathing, because no living being can survive without oxygen. In humans, Iron is the delivery driver that ensures oxygen reaches every cell. This vital task is carried out through hemoglobin, a protein in red blood cells (RBCs) that binds oxygen molecules and transports them to tissues. It’s the iron in hemoglobin that not only gives blood its characteristic red color but also serves as the central metal ion in heme. Heme is the active component of hemoglobin, consists of four pyrrole rings with nitrogen arranged around a ferrous (Fe²⁺) ion at its core. When combined with the globin protein, it forms hemoglobin, the key player in oxygen transport. The iron ion’s ability to shift between the Fe²⁺ and Fe³⁺ oxidation states allows it to bind and release oxygen molecules efficiently, sustaining life [5].

Interestingly, iron is not the only player for oxygen transport throughout the animal kingdom; some invertebrates use hemocyanin for oxygen transport. Unlike hemoglobin, which contains iron, hemocyanin contains copper. When copper shifts between its 1+ and 2+ oxidation states, it binds oxygen and surprisingly, it gives a striking blue color to the blood [7].

Iron’s role extends beyond hemoglobin. It is also a crucial component of myoglobin, a muscle protein that stores oxygen for quick bursts of activity. Myoglobin’s structure is similar to that of hemoglobin, but it consists of only a single globin subunit, unlike hemoglobin, which has four subunits.

Iron isn’t just important for oxygen transport in our blood—it’s also a star player at the cellular level. You’ve probably heard that mitochondria are the powerhouses of our cells, but did you know that iron is crucial to the process that powers them? Inside these tiny organelles, iron is key to the electron transport chain, the pathway that converts the food we eat into energy. Special proteins in the mitochondria contain iron, and these proteins work together to create ATP (adenosine triphosphate), which is the energy currency of every cell in our body. Some of these iron-containing proteins include heme-based cytochrome c and iron-sulfur clusters found in enzymes like NADH ubiquinone oxido-reductase. If iron levels in the mitochondria are too low—or too high—it can cause a cascade of problems, disrupting the production of critical molecules like heme and iron-sulfur clusters, and even damaging the mitochondria themselves. This imbalance can lead to oxidative stress, a condition linked to cell damage and aging. So, the next time you think about energy, remember that iron isn’t just helping your blood carry oxygen—it’s also keeping your cells powered up and ready to go![8]

Iron does much more than just fuel oxygen transport and energy production—it helps to keep our body safe and sharp. Take catalase, for example. This iron-powered enzyme acts like a molecular bodyguard, protecting our cells from oxidative damage by breaking down harmful hydrogen peroxide. Without enough iron, our immune system would have a much harder time fending off infections [9].

But iron doesn’t stop there—it’s also critical for brain development and function. It’s a key cofactor for enzymes involved in the production of neurotransmitters, the chemical messengers that help our nerve cells communicate [10]. So, the next time you’re stuck on a tricky math problem or lose a chess match, don’t blame your brain—maybe it’s just craving a little more iron in your diet!

We all know iron plays a big role in our biology, but guess what? There’s another metal that’s going to surprise you.

Because it’s Copper, the multi-tasker element of our bodies. Copper is the shiny, reddish-brown metal you see in electrical wires and coins. It’s essential for conducting electricity, and without it, modern technology would come to a halt. But did you know that in our body, copper isn’t just about conductivity—it’s a superhero metal!

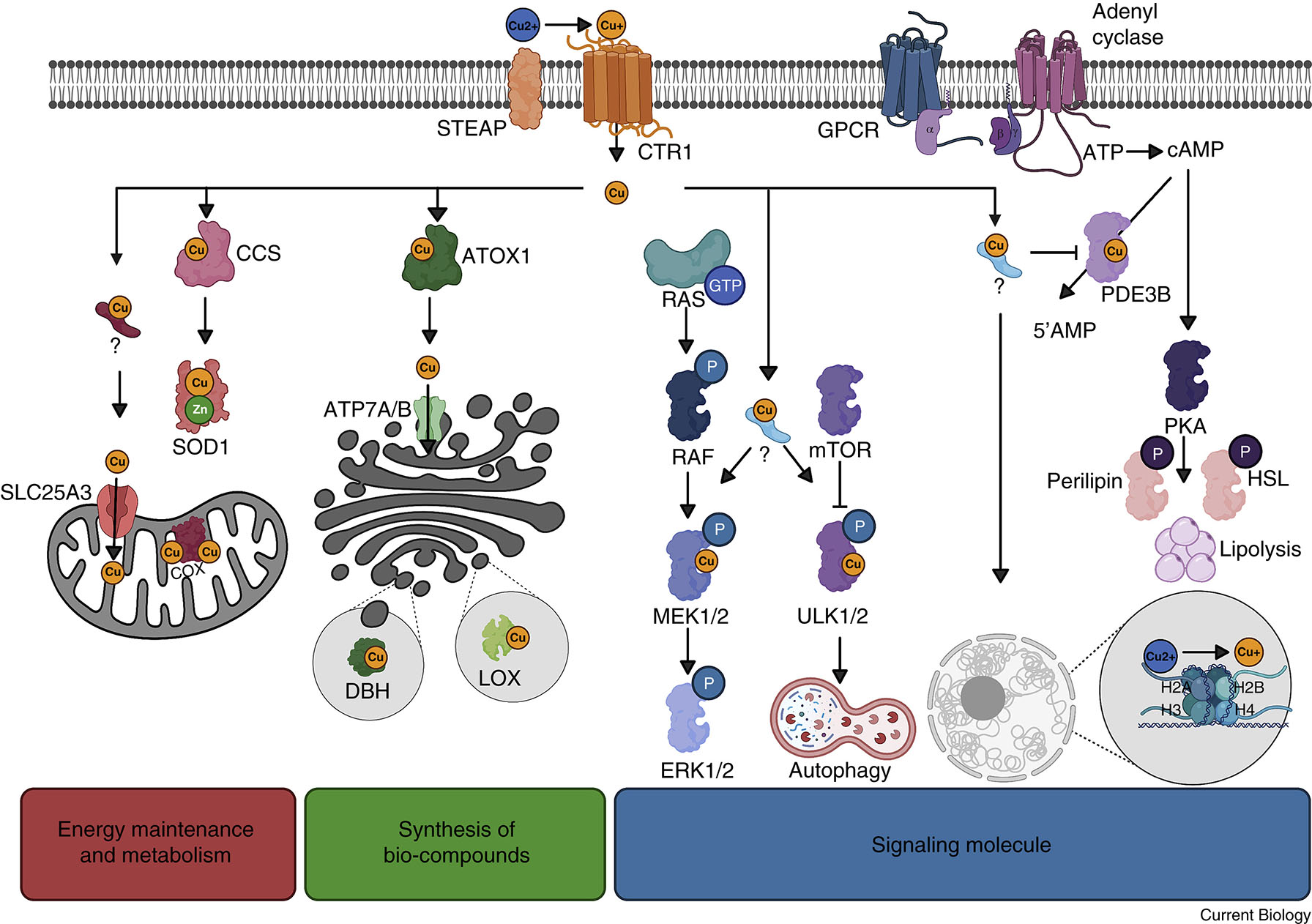

One of copper’s key roles is helping cells produce energy. Inside our cells, copper is a crucial part of cytochrome C oxidase, the final enzyme in the chain of energy production. This enzyme helps create a proton gradient that is essential for generating ATP, which is the cell’s main energy source. ATP is the fuel that powers everything from muscle movement to brain function. Without copper, this process would not work, and our body wouldn’t be able to literally move a muscle [11].

Copper also helps protect our cells. When our cells make energy, they produce reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can be harmful if they build up. Copper helps control these by being part of another enzyme called superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), which neutralizes ROS and keeps our cells safe from damage. Also, copper helps our body use iron properly. Iron is needed for making parts inside our cells that are crucial for energy production. Copper makes sure iron works correctly, ensuring everything runs smoothly inside our cells [11].

Copper helps carry electrical signals between nerve cells, ensuring that your brain and body are always in sync. Copper binds to important receptors in the brain, (like GABAA and NMDA) and also interacts with channels that control calcium flow in nerve cells. When calcium signals are sent, copper is released at synapses (the points where nerve cells meet), helping manage how cells communicate with each other and allowing your brain to adapt and learn. Think of copper as the “connector” that helps everything stay in sync. Without it, your body would have trouble functioning properly, much like a phone without a charger. Too little copper can make you feel tired, while too much can harm your liver. So, it’s important to maintain the right balance of copper for a healthy, energetic life.

Why do we need food and oxygen to survive? Metabolism is the sum of all chemical reactions in your cells that sustain life. These reactions are divided into anabolism, which uses energy to build molecules, and catabolism, which breaks down molecules to release stored energy. Think of it like a LEGO set, food is broken down into its basic building blocks (like proteins, fats, and carbohydrates), which can either release energy or be reassembled into essential body components like muscles or bones.

The energy released during food breakdown is stored in a molecule called ATP (adenosine triphosphate), the cell’s rechargeable battery. When energy is needed, ATP loses a phosphate group, becoming ADP (adenosine diphosphate) and releasing energy. When the cell has extra energy, it recharges ATP by adding a phosphate back to ADP.

Oxygen is essential for many metabolic reactions, especially those that occur in the mitochondria, the cell’s energy powerhouses. Just like a fire needs oxygen to burn, your body needs oxygen to “burn” food and release energy efficiently. This entire process ensures your cells have the energy they need to function [13].

But copper’s contributions go beyond energy. Copper is key in the formation of hemoglobin and collagen which keeps your skin and tissues strong. It strengthens blood vessels and connective tissues by activating Lysyl Oxidase, an enzyme that cross-links collagen and elastin. These proteins give your tissues flexibility and strength, whether it’s your skin, arteries, or bones. Copper also helps produce melanin, the pigment that colors your hair and skin. [4 Fe] So when dealing with an uneven skin tone, stop polishing your face with foundation and concealer, and simply give some copper to your body!

Now, let’s come to the Zinc, the master regulator. Zinc might not be flashy, but it’s involved in over 300 enzyme reactions in your body. Zinc is like a messenger inside and outside of cells, helping to transmit signals. Outside the cell, zinc is stored in small sacs called vesicles and released when needed to interact with special receptors on the cell’s surface. This triggers various processes, like controlling how calcium flows into the cell or how cells grow and survive. Inside the cell, zinc affects many important proteins and enzymes that control activities such as cell movement, energy production, and how cells respond to stress. It can also regulate other messengers like cAMP, which influence immune responses and other vital functions. Essentially, zinc helps cells “talk” to each other and makes sure everything runs smoothly inside the cell.[14].

Zinc is an essential mineral for the body, especially for cell growth, division, and repair. It plays a crucial role in synthesizing DNA and proteins, which are necessary for cells to reproduce and function properly. Zinc also helps activate enzymes that regulate the cell cycle, the process that controls how cells divide. If there is not enough zinc, cell division can slow down or even stop. Zinc is also involved in several signaling pathways that control cell growth. One of these is related to IGF (Insulin-like Growth Factor), a hormone that helps stimulate cell division and growth. Zinc supports the activity of IGF-1 by enhancing its ability to bind to its receptor, which activates a cascade of signals that promote cell proliferation. In addition, zinc plays a role in the structure of microtubules, which are important for cell division and maintaining cell shape. Without zinc, the assembly of these structures can be impaired, affecting the ability of cells to divide properly. Overall, zinc is vital for maintaining healthy cell functions, especially for growth and repair [14].

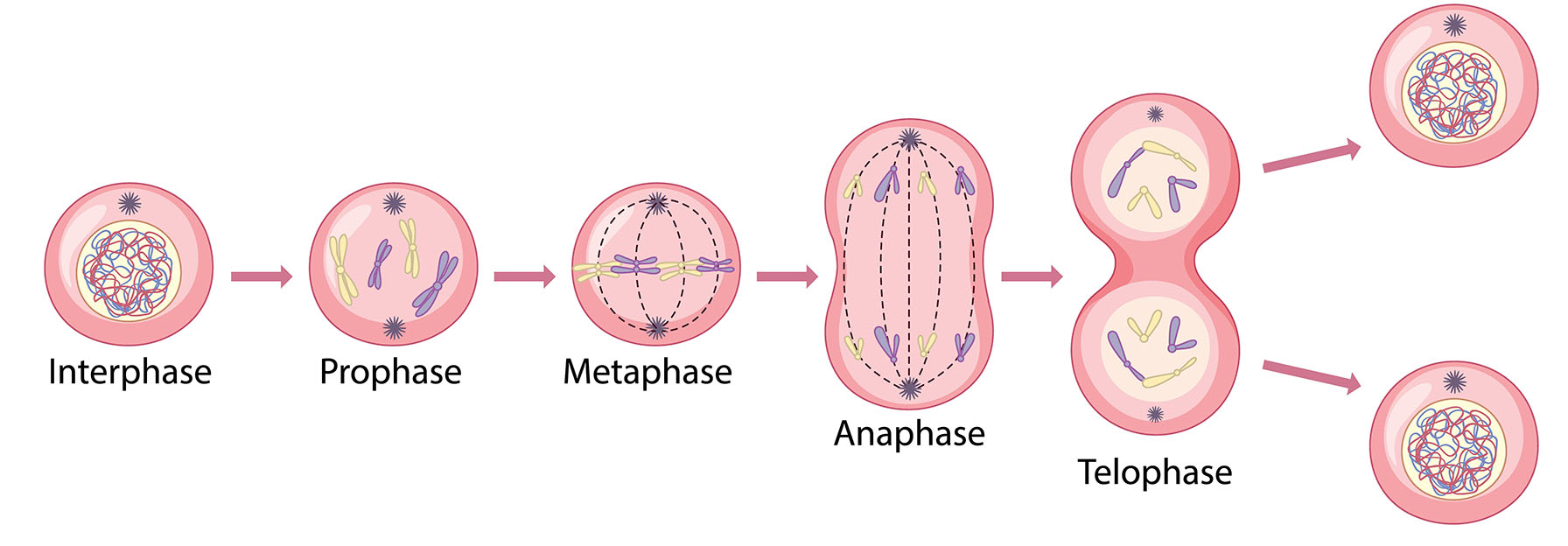

Cell division is far more crucial to our lives than we often realize. The very process that drives reproduction in single-celled organisms is also the foundation for our body’s growth and ability to heal. In unicellular organisms, binary fission is the key to life’s continuation, one cell divides to create two identical cells, forming a whole new organism. In our bodies, the process is slightly different but just as essential. Mitosis enables us to grow, repair, and regenerate. Each time a cell divides, it forms two identical daughter cells, allowing us to grow from a single fertilized egg into a fully developed organism and heal wounds as they occur [15].

For example, when you get a cut, the cells around the wound begin to divide rapidly, helping to form new tissue and close the wound. But this process isn’t just about growth; it’s critical for replacing damaged or dead cells, ensuring the body stays healthy and functions properly. While mitosis ensures that daughter cells maintain the same number of chromosomes, meiosis—another type of cell division—reduces the chromosome number by half, which is necessary for the creation of egg and sperm cells, enabling reproduction. Together, these processes maintain the balance of life, ensuring that organisms can grow, repair, and reproduce across generations [16].

It generally protects cells from dying by influencing proteins that control cell survival, like caspases (enzymes that cause cell death). If there isn’t enough zinc, these proteins become more active, leading to cell death in types of cells like brain and liver cells. However, too much zinc can be harmful. High levels can damage cell function by affecting mitochondria, the cell’s energy source, leading to death. The ability of cells to live or die depends on how well they control zinc levels and how proteins respond to it. Zinc’s effect on cell death also varies. For example, in cancer cells, zinc can promote death, but in normal cells, it often prevents it. Zinc interacts with proteins like P53 and NF-kB, which are involved in regulating cell death, making its role in apoptosis complex and dependent on factors like zinc concentration and cell type [17].

Zinc plays a crucial role in DNA repair and protection. It helps prevent DNA damage by acting as an antioxidant, neutralizing harmful molecules that can cause mutations. Zinc is involved in the functioning of several enzymes that repair damaged DNA, including those that fix base or strand breaks. Without enough zinc, these repair processes become less effective, leading to more DNA damage, oxidative stress, and potential diseases like cancer. Essentially, zinc supports the repair machinery in cells, helping to maintain the integrity of our genetic material [14].

References

- D. Prialnik, An introduction to the theory of stellar structure and evolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- H. Chen, S. Vitale, and F. Foucart,

The Relative Contribution to Heavy Metals Production from Binary Neutron Star Mergers and Neutron Star–Black Hole Mergers,

The Astrophysical Journal Letters, vol. 920, no. 1, p. L3, 2021. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ac26c6 - J. Korenaga and S. Marchi,

Vestiges of impact-driven three-phase mixing in the chemistry and structure of Earth’s mantle,

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 120, no. 43, p. e2309181120, 2023. doi:10.1073/pnas.2309181120 - C. published,

Asteroids May Have Brought Precious Metals to Earth,

Sep. 7, 2011. [Online]. Available: https://www.livescience.com/15938-earth-precious-metals-space-origin.html [Accessed: Nov. 30, 2024]. - J. Bonaventura, C. Bonaventura, and B. Sullivan,

Hemoglobins and hemocyanins: Comparative aspects of structure and function,

Journal of Experimental Zoology, vol. 194, no. 1, pp. 155–174, 1975. doi:10.1002/jez.1401940110 - P. Dahal,

Hemoglobin: Structure, Types, Functions, Diseases,

Aug. 25, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://microbenotes.com/hemoglobin/ [Accessed: Dec. 1, 2024]. - D. Lutz,

The Many Colors of Blood,

ChemMatters, 2010. [Online]. Available: https://www.acs.org/content/dam/acsorg/education/resources/highschool/chemmatters/issues/best-of-chemmatters/sample-lesson-plan-the-many-colors-of-blood.pdf - G. Duan, J. Li, Y. Duan, C. Zheng, Q. Guo, F. Li, J. Zheng, J. Yu, P. Zhang, M. Wan, and C. Long,

Mitochondrial Iron Metabolism: The Crucial Actors in Diseases,

Molecules, vol. 28, no. 1, p. 29, 2022. doi:10.3390/molecules28010029 - K. Jomova, M. Makova, S. Alomar, S. Alwasel, E. Nepovimova, K. Kuca, C. Rhodes, and M. Valko,

Essential metals in health and disease,

Chemico-Biological Interactions, vol. 367, p. 110173, 2022. doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2022.110173 - A. Florea, D. Büsselberg, and D. Carpenter,

Metals and Disease,

Journal of Toxicology, vol. 2012, pp. 1–2, 2012. doi:10.1155/2012/825354 - E. Gaier, B. Eipper, and R. Mains,

Copper signaling in the mammalian nervous system: Synaptic effects,

Journal of Neuroscience Research, vol. 91, no. 1, pp. 2–19, 2013. doi:10.1002/jnr.23143 - T. Tsang, C. Davis, and D. Brady,

Copper biology,

Current Biology, vol. 31, no. 9, pp. R421–R427, 2021. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.03.054 - L. Ruiz, A. Libedinsky, and A. Elorza,

Role of Copper on Mitochondrial Function and Metabolism,

Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences, vol. 8, p. 711227, 2021. doi:10.3389/fmolb.2021.711227 - M. Costa, A. Sarmento-Ribeiro, and A. Gonçalves,

Zinc: From Biological Functions to Therapeutic Potential,

International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 24, no. 5, p. 4822, 2023. doi:10.3390/ijms24054822 Cell Division: Stages of Mitosis | Learn Science at Scitable,

[Online]. Available: http://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/mitosis-and-cell-division-205 [Accessed: Dec. 1, 2024].- A. Ye and T. Maresca,

Measuring mitotic forces,

in Methods in Cell Biology, Elsevier, 2018, vol. 144, pp. 165–184.[Online]. Available: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0091679X18300074 [Accessed: Dec. 1, 2024]. - B. Chen, P. Yu, W. Chan, F. Xie, Y. Zhang, L. Liang, K. Leung, K. Lo, J. Yu, G. Tse, W. Kang, and K. To,

Cellular zinc metabolism and zinc signaling: from biological functions to diseases and therapeutic targets,

Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, vol. 9, no. 1, p. 6, 2024. doi:10.1038/s41392-023-01679-y